Some time ago I made an Instagram post comparing these two languages, which I started simultaneously during the hard lockdown in spring 2020 (you can see it on @chiara.klara.claire, as a summary of this article). With this article I’ll dig in deeper and talk about more aspects.

A short overview of Icelandic and Finnish main characteristics:

Icelandic belongs to North Germanic languages, as Swedish, Norwegian and Danish and Faroese, the closest of all to it (learn how to tell them all apart) . It is still very close to what Old Norse was and retained a highly inflected grammar and ð/þ.

Finnish is an Uralic language, sister language of Estonian and related to Sámi languages but completely unrelated to its Scandinavian Neighbors. Its grammar is as complex as Icelandic but as an agglutinative language, lacking however genders.

In a language difficulty ranking 1-5 with 5 being the hardest, Icelandic was category 4 and Finnish between 4 and 5.

You can find useful language resources at the end of this article!

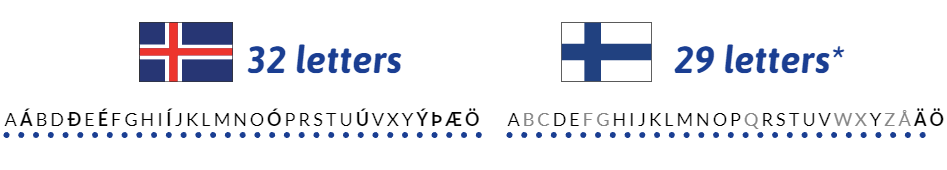

Alphabets & ortography

- Icelandic Ðð (eth) is as “th” in the, Þþ (thorn) as in think. the former is also present in Faroese, its closest language

- a, á, e, é, i, í, o, ó, u, ú, y, ý, æ, ö are all the vowels, each is a distinct letter of the Icelandic alphabet

- c, q, w are not present in Icelandic. Z was removed in 1973 and replaced with S in words which had it. It is still present in some historic names as the Verzló school in Reykjavík.

- Finnish actually uses only 21 of the 29 letters in its alphabet, which derives from Swedish: b, c, f, g, q, w, x, z, å are not present in native Finnish words. For example, the Swedish name of Turku, city with a significant number of Swedish speakers, is Åbo.

- Finnish is the only language in which the frequency of vowels exceeds that of consonants, and both are often doubled: suosittelette. vaapukka, terveellistä, laatikko, karjalanpiirakka. With its relatively small inventory of letters being often doubled, many words change meaning with one letter: muta “mud”, mutta “but”, muuta “other”, muuttaa “to move”

Both languages use a lot of long compound words (common in most Germanic languages) as a way to construct new words. Those long stretches of letters might look obscure, but if you break them into smaller words they are quite normal: Icelandic volcano Eyjafjallajökull is just “island-mountain glacier”. An example in Finnish could be lumipallosotatantere = “snowball fight field”, English would be no different if it removed spaces after all!

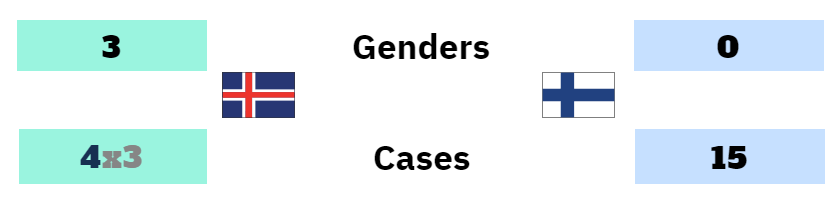

Grammar

This is what Finnish and Icelanidc are most (in)famous for, both have an arguably complicated grammar, but more or less hard depending on the aspects.

In Icelandic and Finnish words change depending on their role in a sentence, with the so-called cases. Although to a much smaller extent cases exist in English too, in personal pronouns: she becomes her when it’s an object. In the following table you can see how cases change words in these two languages:

| (a) beatiful country | in (a) beautiful country | to (a) beautiful country | from (a) beautiful country | |

| Icelandic | fallegt land | í fallegu landi | til fallegs lands | frá fallegu landi |

| Finnish | kaunis maa | kauniissa maassa | kauniiseen maan | kaunista maasta |

Icelandic has 4 cases: nominative, accusative, dative, genitive (nefnifall, þolfall, þágufall, eignarfall) – familiar if you know German or Latin – in which nouns, pronouns and adjectives are declined differently depending on gender: (masculine, feminine, neuter), with weak or strong nouns, and number. Icelandic has no articles but it does have definite forms, which as in Scandinavian languages is marked in the end of the nouns: maður= (a) man, maðurinn = the man). More detailed info here

| function | M* | pl. | F* | pl. * | N* | pl. * | |

| nom. | subject | -i; -ur, ll.. | -ar | -a; – | -ur; -ir | -a; – | -u; – |

| acc. | object | -a; -, -l..f | -a | -u; – | -ur; -ir | -a; – | -u; – |

| dat. | indirect object | -a; -um, -i | -um | -u; – | -um | -a; -i | -um |

| gen. | possession | -a; -s | -a | -u; -ar | -a | -a; -s | -a |

Finnish uses many suffixes instead of prepositions, with a total of 15 cases, in which nouns, pronouns, adjectives, numerals are declined. The good news is that Finnish has no genders nor articles: even the personal pronoun hän means both he and she.

The 15 cases can be divided into five groups:

- Basic cases: nominative, genitive, accusative,

- General local cases: partitive, essive, translative,

- Interior local cases: inessive, elative, illative,

- Exterior local cases: adessive, ablative, allative

- Means cases (rarely used, mostly in fixed expressions): abessive, comitative, instructive

| # | case | suffix | example | meaning |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | nominatiivi | – : t | talo : talot | house |

| 2 | genetiivi | -n : -jen … | talon : talojen | of (a) house |

| 3 | essiivi | -na : -ina | talona : taloina | as a house |

| 4 | partitiivi | -(t)a : -ja … | taloa : taloja | house (as an object) |

| 5 | translatiivi | -ksi : -iksi | taloksi : taloiksi | to a house |

| 6 | inessiivi | -ssa : -ssa | talossa : taloissa | in (a) house |

| 7 | elatiivi | -sta : -ista | talosta : taloista | from (a) house |

| 8 | illatiivi | -an, -en .. : -ihin, -isiin | taloon : taloihin | into (a) house |

| 9 | adessiivi | -lla : -illa | talolla : taloilla | at (a) house |

| 10 | ablatiivi | -lta : -ilta | talolta : taloilta | from (a) house |

| 11 | allatiivi | -lle : -ille | talolle : taloille | to (a) house |

| 12 | abessiivi | -tta : -itta | talotta : taloitta | without (a) house |

| 13 | komitatiivi | -ine- | taloine(ni) | (together) with my house(s) |

| 14 | instruktiivi | -n : -in | taloin | with (the aid of) house |

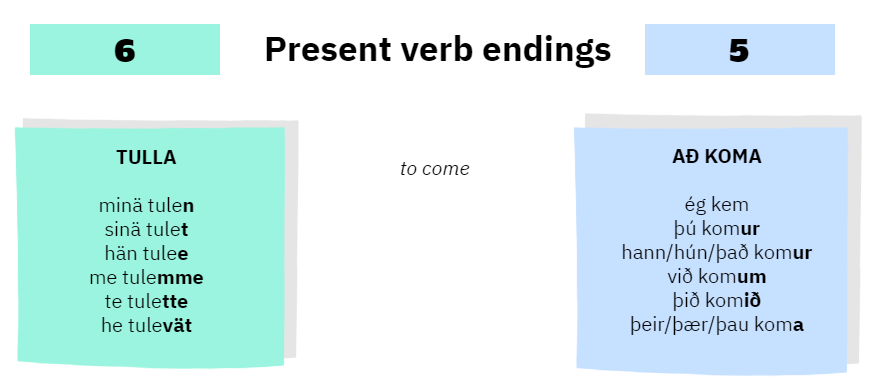

Verbs are divided in both languages into groups, 3 in Icelandic and 6 in Finnish, depending on which conjugations slightly change, but are not (in my opinion) much harder than in Romance languages as Italian and French. They have different endings for each person, and the infinitive form is sometimes not immediately recognisable knowing a conjugated form.

Vocabulary

As you might have already figured out, Icelandic is more accessible with knowledge of (North) Germanic languages, while Finnish will look completely unfamiliar unless you speak an Uralic language:

| Icelandic | Scandinavian (se/dk/no) | German | Dutch | Finnish | |

| apple | epli | äpple/æble/eple | Apfel | appel | omena |

| book | bók | bok | Buch | boek | kirja |

| hair | hár | hår | Haar | haar | hiukset |

| house | hús | hus | Haus | huis | talo |

| mother | móðir | mor | Mutter | moeder | äiti |

| night | nótt/nátt | natt | Nacht | nacht | yö |

| stone | steinn | sten | Stein | steen | kivi |

| that | það | det | das | dat | se |

| word | orð | ord | Wort | woord | sana |

However, due to its history under Swedish rule -other than having the Scandinavian country as neighbour- Finnish adopted many loanwords from and through Swedish, adapting them to its spelling and pronounciation:

- katu – gata (street)

- koulu – skola (school)

- sokeri – soker (sugar)

- tuoli – stol (chair)

- suklaa – choklad (chocolate)

- pankki – bank

- kahvi – kaffe (coffee)

During the 19th century, Icelandic started avoiding borrowing neologisms found in most European languages with its Linguistic purism policy, creating new vocabulary with Old Norse roots for new concepts: Theatre is Leikhús, “acting house”; AIDS is alnæmi, from al “all/complete” and næmi “sensitive”, which is what the disease really is about.

Finnish also has a good number of neologisms with native words when most European languages use a common Latin/Greek or English form:

| Icelandic | Finnish | |

| grammar | málfræði “language science” | kielioppi “language study” |

| electricity | rafmagn “amber power” calquing the Greek root | sähkö based on sähähtää “to sizzle (briefly)” + säkenöidä “to sparkle” |

| phone | sími originally “cord” | puhelin “I chatter” |

| computer | tölva (computer)=tala+völva “number seeress” | tietokone “knowledge/data machine” |

| film | kvikmynd “alive/moving picture” | elokuva “life picture” |

As mentioned before Finnish did anyway adopt many words common in European languages, while Icelandic has words of its own, probably also thanks to its geographical isolation:

| Icelandic | Scandinavian | Finnish | |

| idea | hugmynd “mind picture” | idé | idea |

| comet | halastjarna “tail star” | komet | komeetta |

| psychology | sálfræði “soul study” | psykologi | psykologia |

| history | sagnfræði | historia/historie | historia |

| philosophy | heimspeki | filosofi | filosofia |

| bus | strætó | buss | bussi |

| helicopter | þyrla | helikopter | helikopteri |

| president | forseti | president/præsident | presidentti |

| normal | eðlilegt | normal | normaali |

| immune | ónæmur | immun | immuuni |

| alcohol | áfengi | alkohol | alkoholi |

Pronunciation

Icelandic: Although not as inconsistent as English, in Icelandic different positions in the words or letter combinations make the same consonants sound differently, with many variations which at least for me took long to grasp and I am often in doubt about the pronounciation of Icelandic words. Here is a list of tricky features from wikibooks

- HV is pronounced as KV, (or as Scots WH in some areas)

- LL is often pronounced something like tl. MM and NN as pm and tn.

- KK, PP, and TT are pronounced with an h sound to their left. Pre-aspirated tt is analogous etymologically and phonetically to German and Dutch cht (Night-Icelandic nótt, German/Dutch Nacht.

- If a K is followed by a t, it is pronounced similarly to a Spanish j (e.g. lukt – lantern). Likewise, a P followed by a t changes into an f sound (e.g. Að skipta – to shift). F in the middle of a word is often pronounced as a v (e.g. Að skafa – to shave), FF is pronounced as English F.

- Word-final voiced consonants are devoiced pre-pausally, so that dag (‘day (acc.)’) is pronounced as [ˈta:x] and dagur (‘day (nom.)’) is pronounced [ˈta:ɣʏr̥

- I and Y share the same pronunciation, as do Í and Ý.

Finnish: Extremely consistent and read just like it is written: Each grapheme (independent letter), represents almost exactly one phoneme (sound).

- Double consonants can be challenging for English speakers among others, and failing to pronounce them correctly can result in confusion with other words.

- Some vowel combinations can be tricky for your tongue: yö, pyöreä (with y pronounced as ü in German).

With little exposure I was confident in pronouncing Finnish, while Icelandic requires much more effort & time, this might be influenced by the fact that Italian phonology is more similar to Finnish, and double consonants are not problematic to me as an Italian native speaker.

Language variations

Icelandic has very small dialect variations, presumably due to its strong writing culture throughout history. However, some local pronunciation variants exist.

Finnish has dialects divided into two distinct groups, Western and Eastern. Finnish dialects are largely mutually intelligible and operate on the same phonology and grammar, not going too far from standard Finnish.

What Finnish is mostly known for is however the distinction between the two registers: the formal, written form Kirjakieli “book language” and Puhekieli “spoken language”. The former is used in written texts and formal situations like political speeches and newscasts, the latter is the main variety of Finnish used in everyday speech, popular TV, radio shows and at workplaces. In Puhekieli words are often shortened: minä olen “I am” becomes mä oon, anteeksi “excuse me” drops the last i and so on.

Conclusions

Both languages can be pretty challenging, with a significant amount of grammar one can hardly just absorb by practicing as in my experience it was with languages as Dutch and Swedish. What I do think is that practicing and paying attention to certain features can be more helpful than only focusing on repeating declensions without context, and I try to mix both. That being said, Icelandic and Finnish are my “slow” languages with Japanese, and at the moment I’m trying to proceed with textbooks once a month, trying to practice with little things as apps and learning/translating things I see here and there on social media.

I personally find Finnish a bit easier per se, since it has no arbitrary gender and different declensions connected to it, a rather easy pronounciation and so on. However, since I speak Germanic languages, I study (& understand!) Icelandic with much more ease and find myself more easily lost in Finnish, for now at least.

Have you tried studying these languages? If both, which one did you think was harder?

p.s. Perse means “ass” in Finnish and Estonian so maybe don’t say per se too often when talking to Finns.

Learning resources

You find many free, online resources for Finnish and Icelandic on my Language Resources page, other than all for mant other languages.

Sources

- Sanders, Ruth H. The languages of Scandinavia (2017) The University of Chicago Press, p. 99-100: Finnish sound structure

- Wikipedia in English, Danish, Norwegian

More articles:

5 symbols of Sami culture

Sámi people, indigenous people of North Scandinavia, have a distinct culture, symbolised by its unique flag and traditional clothing, and part of it are Duodji handicrafts and unique musical expression through yoik.

The best Scandinavian language to learn

How to choose the language to study among Swedish, Danish and Norwegian

Novels and books to study Nordic languages in 2026

my 2026 language plans with books: continue reading Swedish novels and Norwegian non-fiction, and studying Finnish.

4 thoughts on “Icelandic and Finnish: the hardest Nordic languages”