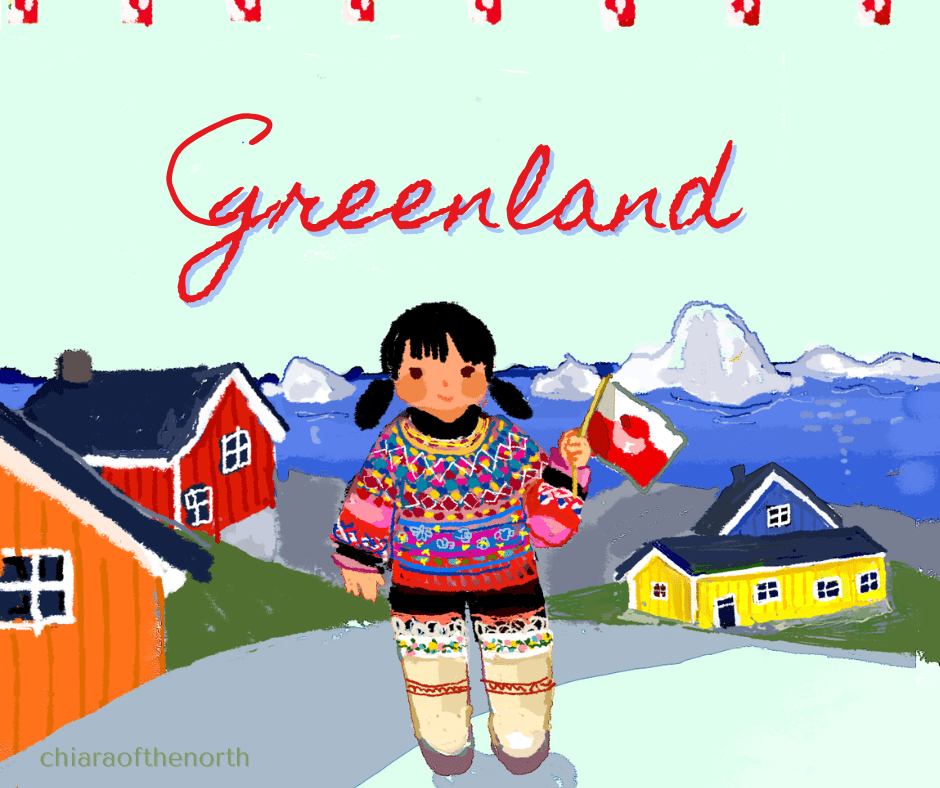

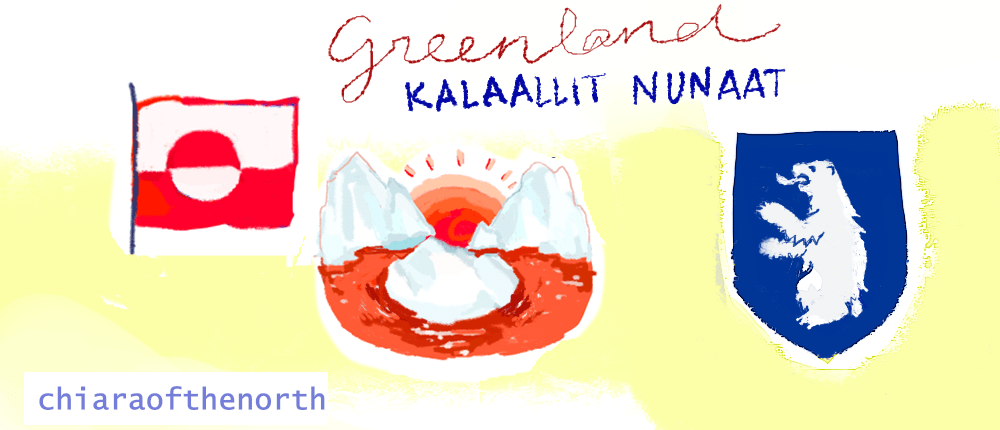

Many have heard of Greenland lately because of what is going on in the world. Here is an introduction to its culture and history, with iconic aspects from this Arctic nation.

Greenland – Kalaallit Nunaat – an Inuit nation between the Vikings and Colonisation

Most of Greenland’s population – the Kalaallit – are Inuits, the indigenous peoples of the Arctic, from North America to Siberia. Although the current Greenlanders’ ancestors, the Thule people, migrated from Alaska around 1000 years ago, Inuits were already present in Greenland in 2500 BC.

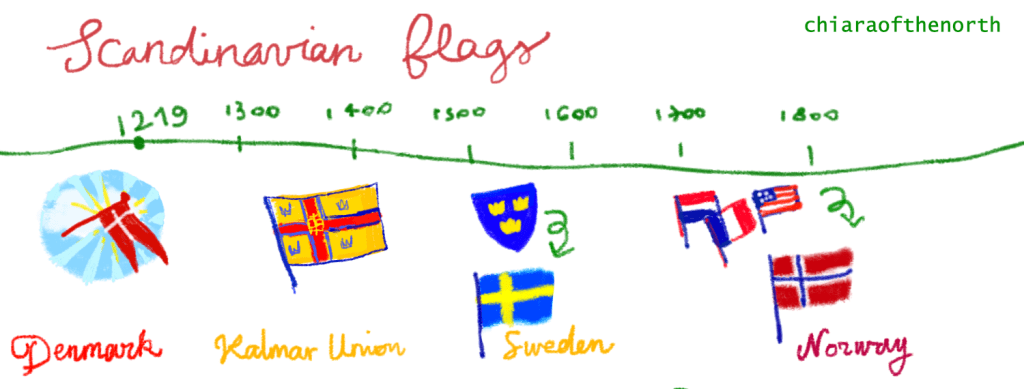

Greenland also had Norse inhabitants for a while – Its norse name Grønland, ‘green land’ was given by Erik den Røde, arriving around 1000 a.D after being exiled from Iceland. Norsemen left around 1400, probably due to the worsened climate conditions of the little ice age. A sign of the Norse settlement are the ruins of the Hvalsey church.

The Scandinavians returned with the Danish colonization from the 1700s, beginning with an expedition to find remaining Norse inhabitants. This time led to suppression and attempts to westernize its people, and despite this, Greenland now proudly preserves its Inuit culture, with its language, traditional clothing, and in its flag.

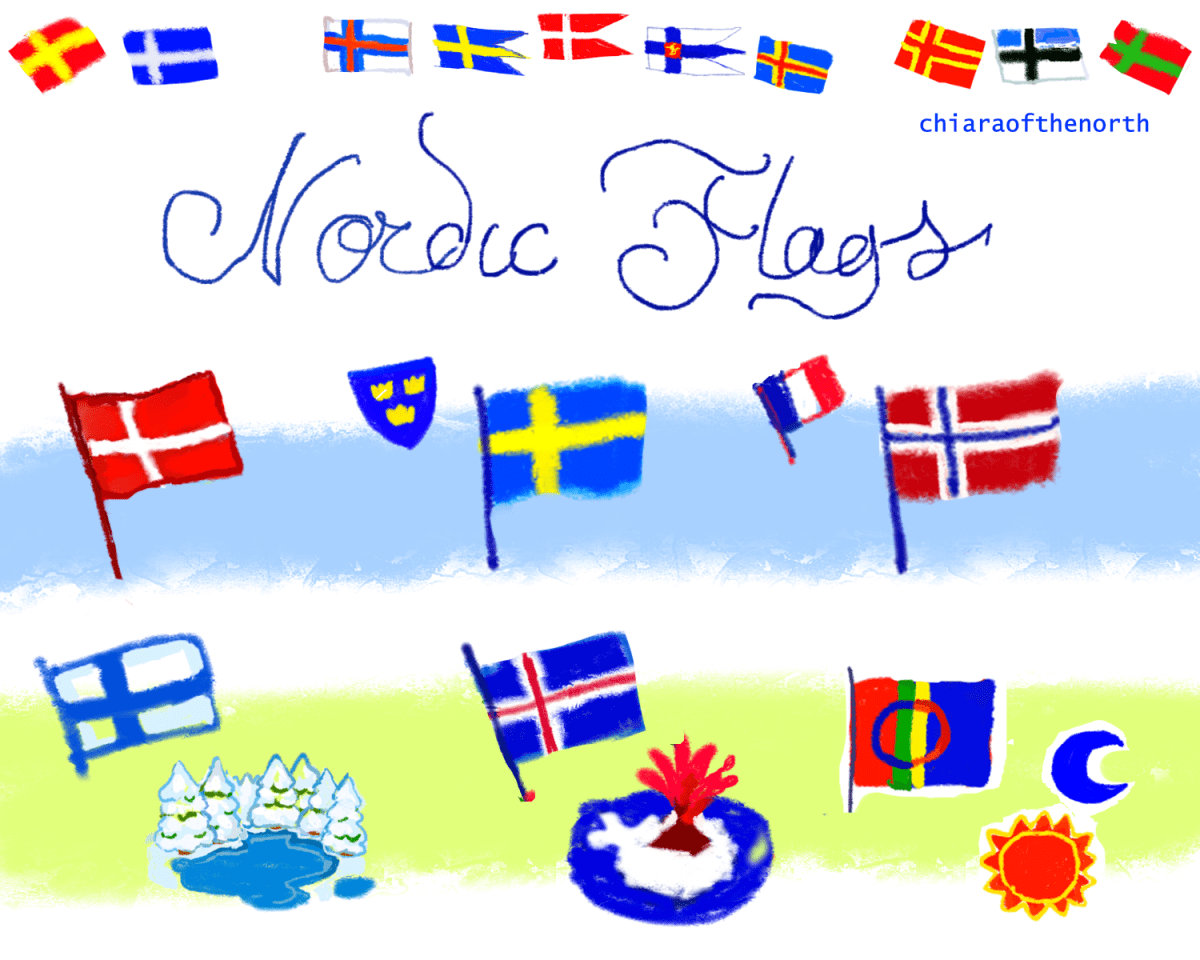

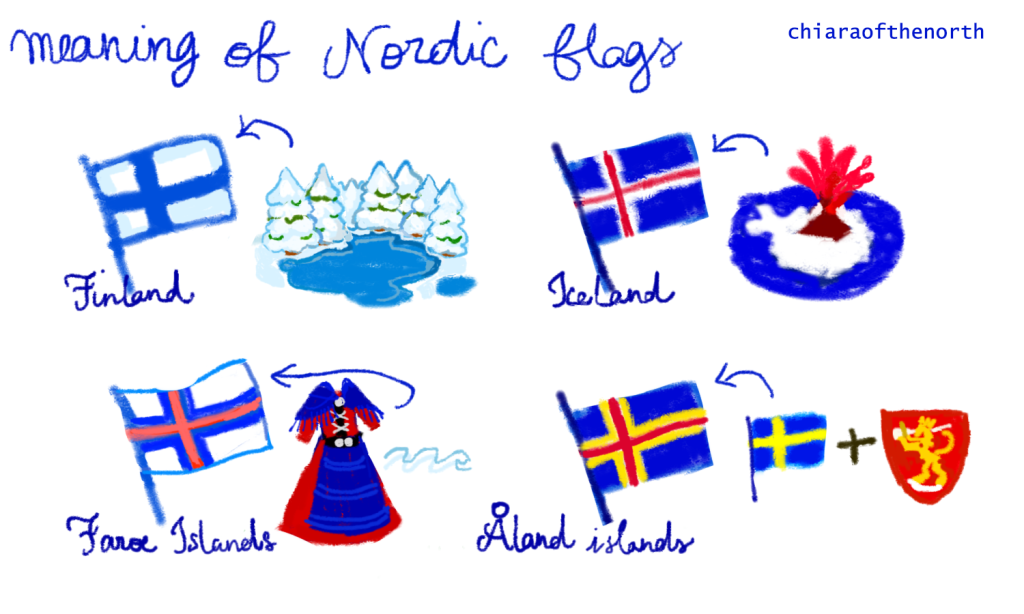

Flag and coat of arms of Greenland

The Greenlandic flag is called Erfalasorput (‘our flag’) and was introduced in 1985, flying for the first time on Greenland’s national day, Summer Solstice.

It symbolizes the sun rising in the arctic Greenlandic landscape, on a light midsummer sky. The red-white colors reference the Danish flag.

It was designed by the Greenlandic artist Thue Christiansen (1940-2022), and was voted as the winner among many other concepts, in particular against a Nordic cross.

Greenlandic Language

the Greenlandic Inuit language, Kalaallisut, is spoken by around 50.000 people – the majority of Greenland’s population – While Danish is taught and spoken as a second language. Greenlandic belongs to the Eskimo-Aleut languages, spoken by indigenous peoples of the arctic area. Loanwords from Greenlandic present in all languages are kayak and anorak.

A distinctive feature is that a single word can express what in English and most European languages would be an entire sentence: Silagissiartuaarusaarnialerunarpoq means “The weather will slowly and gradually become good again”…

Greenlandic incorporated many loanwords from the Danish language (and western culture): biili (bil – car), iipili (æble – apple), juulli (jul – Christmas), as well as greeting as“kumoorn” (god morgen – good morning).

A more detailed post about the Greenlandic language will follow!

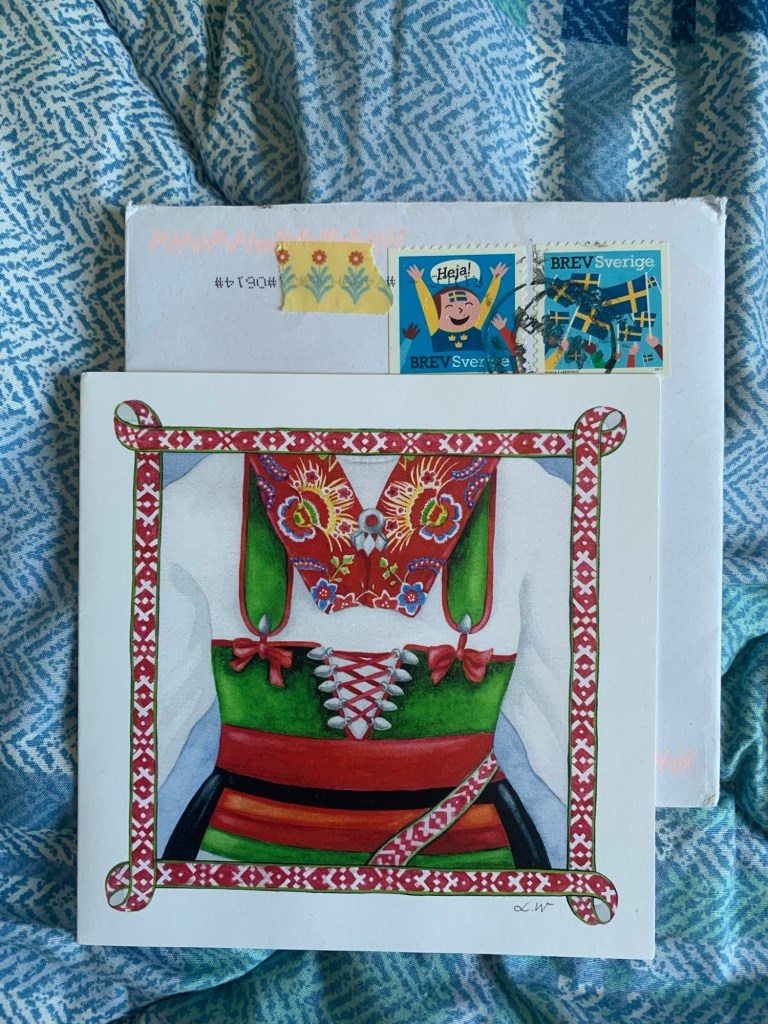

Greenlandic national costume

The Greenlandic national costume – probably the only women’s folk costume in the world with pants instead of a dress or skirt! – is worn on special occasions and is a symbol of Greenlandic identity.

Besides festive days as Christmas/Easter, Weddings, confirmations and Birthdays (on a child’s first birthday in particular), the national costume is worn on Greenland’s National Day (21st June, summer Solstice), and typically by children on their First day of school.

The national costume features a top, pants, and kamik boots. Anorak is the name of the top’s outer! Much is made with sealskin, which was the only material used for clothing until fabric were introduced by Europeans in the 17th Century.

Follow for more info about the culture and language of Greenland!

An introduction to Estonian: sister language of Finnish

Estonian is a Finnic language, sharing many similarities with its ‘bigger’ sister Finnish, while being unrelated to all their bigger language neighbours

Scandinavian carnival buns (and where to eat them in the Netherlands)

Cream buns are enjoyed in Nordic and Baltic countries during shrovetide, between January and February. Sweden’s classic semla has almond paste, while other countries variations include jam, vanilla cream, and chocolate icing top.

5 symbols of Sami culture

Sámi people, indigenous people of North Scandinavia, have a distinct culture, symbolised by its unique flag and traditional clothing, and part of it are Duodji handicrafts and unique musical expression through yoik.

The best Scandinavian language to learn

How to choose the language to study among Swedish, Danish and Norwegian

Novels and books to study Nordic languages in 2026

my 2026 language plans with books: continue reading Swedish novels and Norwegian non-fiction, and studying Finnish.

Who are Greenlanders? 3 symbols of Greenlandic culture

Discover Greenland, home to the Inuit Kalaallit, and its most iconic aspects as its flag, language and folk costumes. The biggest island of the world has a rich history of indigenous culture intertwined with Norse colonization and later Danish rule.

sources:

- guidetogreenland.com

- lex.dk

- Preciosa-Ornela.com

- Nunatta Katersugaasivia Allagaateqarfialu – Greenland National Museum & Archives

- omniglot

- wiktionary