Swedish folk costumes, Folkdräkter, are an important part of a Swedish cultural heritage, and are symbols for local and national identity. There are 840 different variations (550 female outfits and 290 male ones). Some of them have a rather long history, dating back from the 17th century. Members of the Swedish royal family wears a blue and yellow dress with daisy decorations on some occasions – that dress is much more recent!

Different types of Swedish folk costume

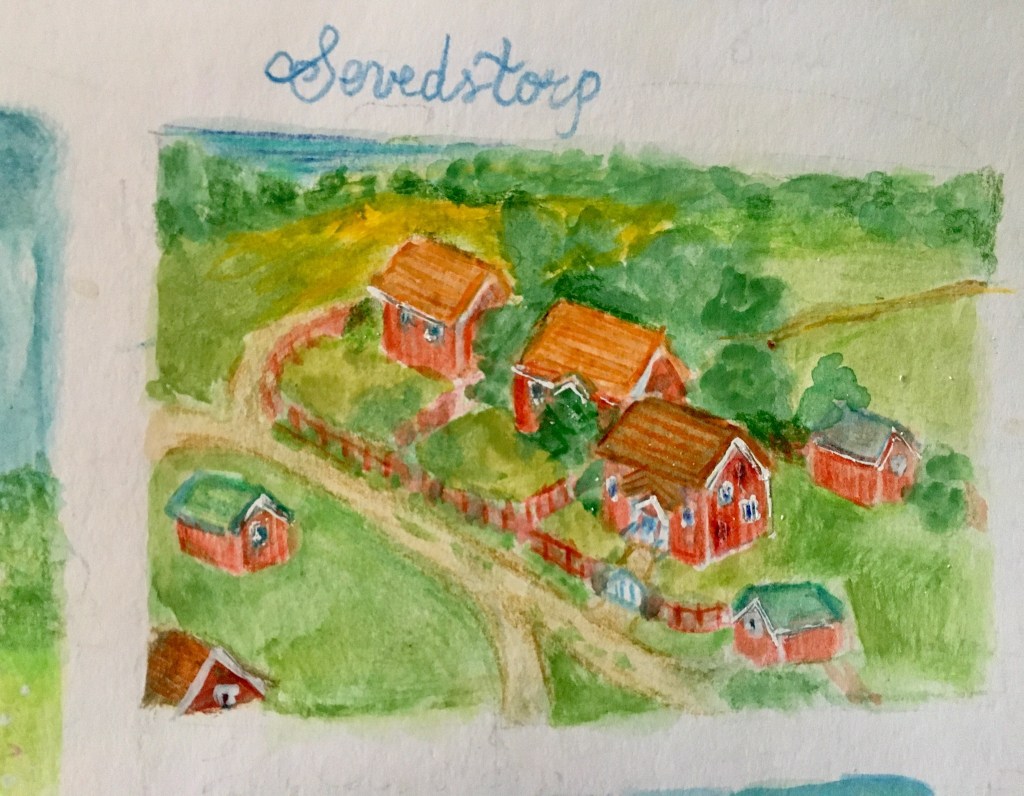

Swedish folk costumes vary by region of origin, but in some they are more common, Dalarna has a very rich folk costume culture for example.

Each district had its own tailor, and some areas with natural boundaries and good communications within the district itself but poorer connections with the outside world would develop their own designs. Among typical features are flower patterns and headgear of all kinds, from bonnets to horn-shaped hats.

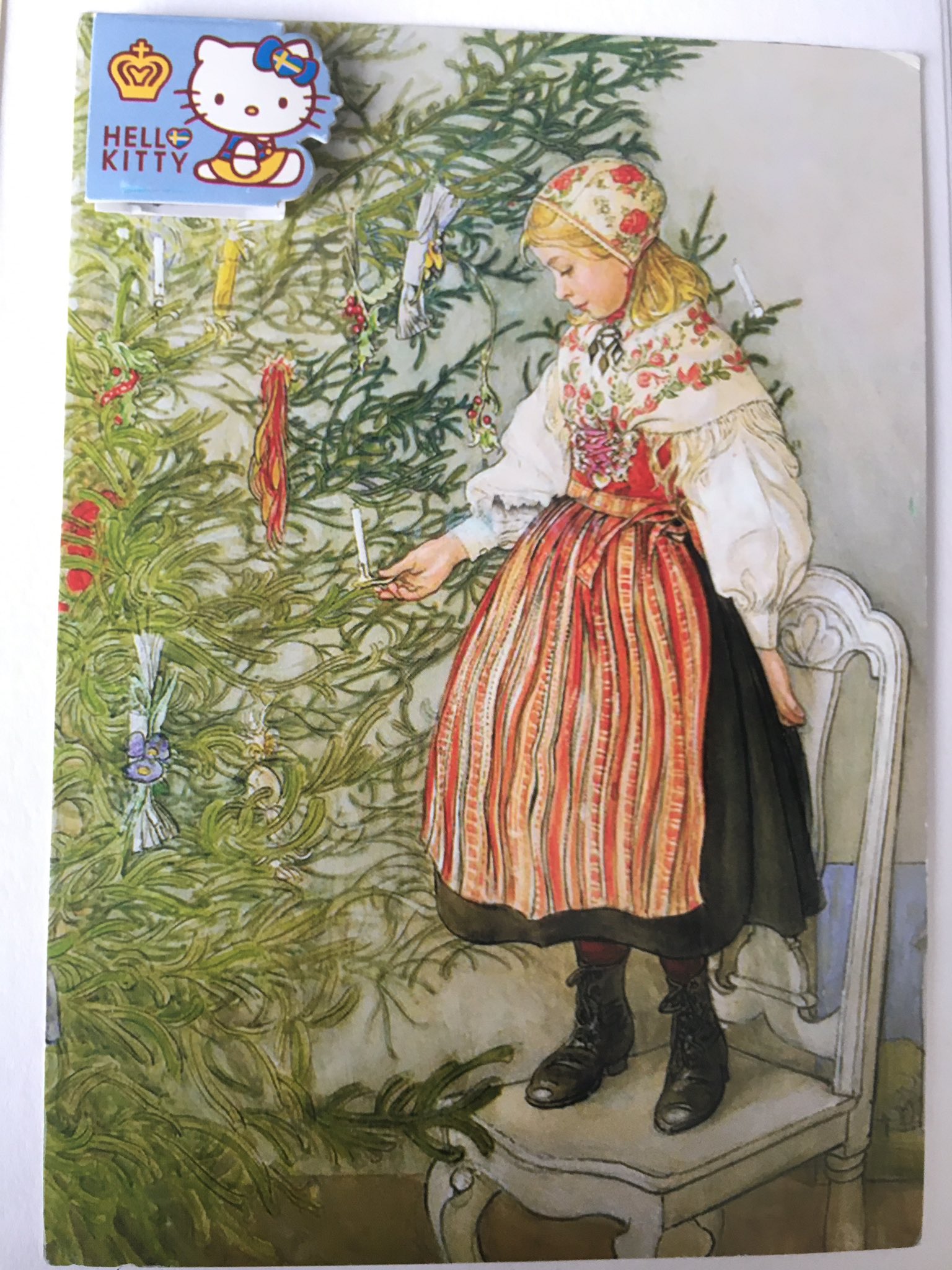

in the 1850s, with the industrialization of Sweden, folk costumes started to be abandoned – but around 1900, with the National romantic period, upper classes amused themselves by wearing them. Some artists also depicted them, Among others Jenny Nyström and Carl Larsson:

[…] In addition we need the bright colors of the peasant costumes. They have an invigorating effect on our senses that is all too often under-estimated and they are necessary as a contrast to the deep green pine forest and the white snow

Carl Larsson, from ‘Ett hem’ (A Home)

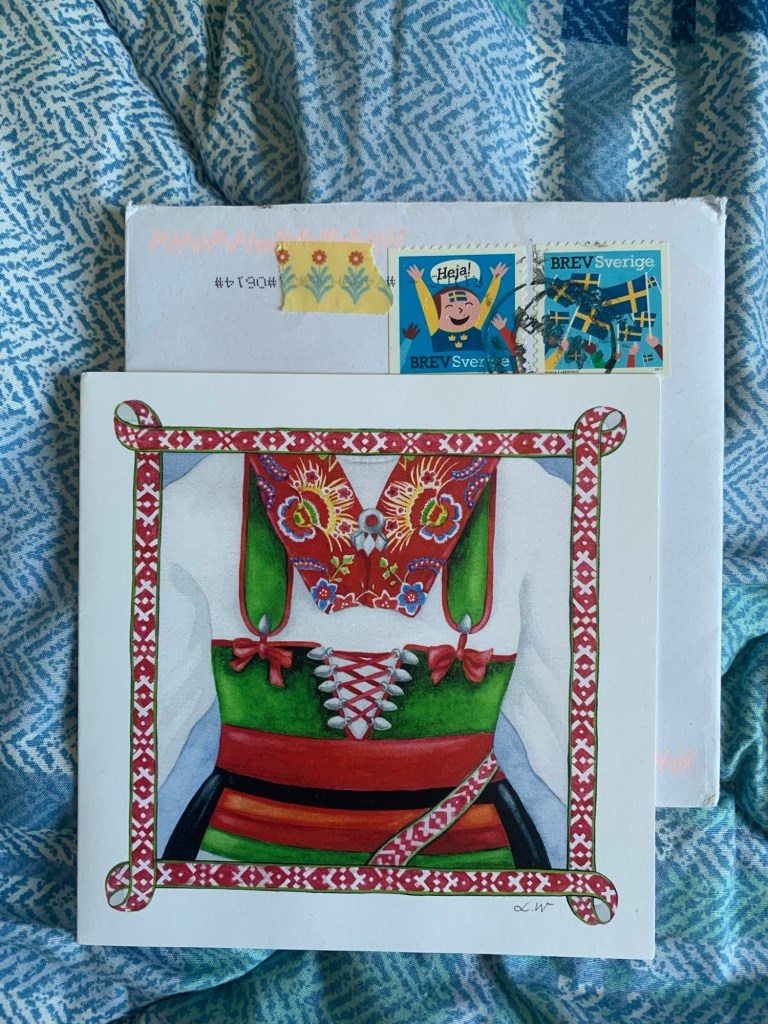

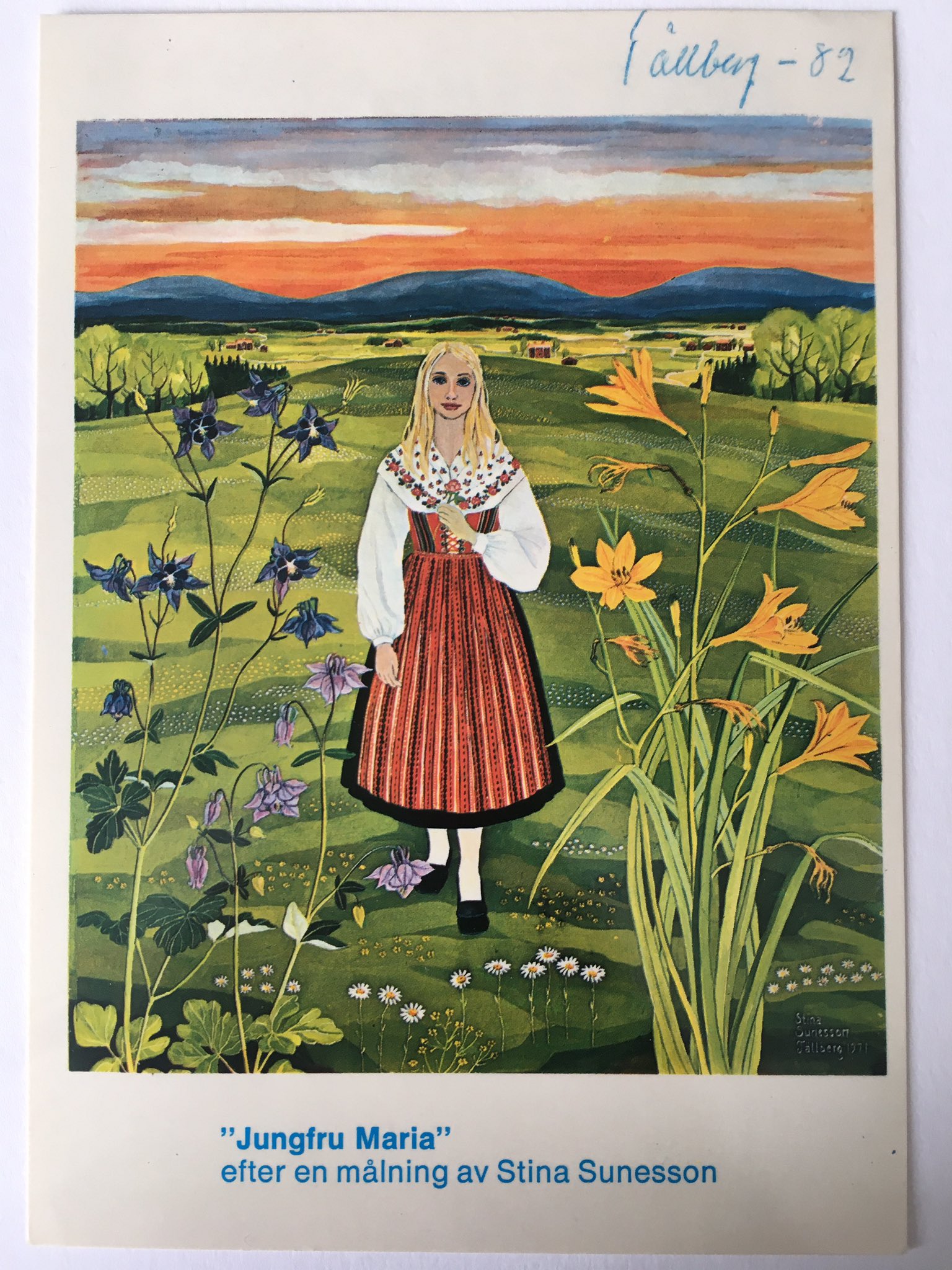

I got a couple postcards from Swedish penpals with paintings featuring folk costumes, by Carl Larsson (and I got a tiny Hello kitty in a svenska dräkten from the same person!) and Stina Sunesson

The invention of the Swedish National dress, Almänna svenska nationaldräkten

In 1983 Queen Silvia wore the Svenska dräkten on Sweden’s National Day, 6th June, starting a tradition. The dress she wore was relatively recent, designed by a woman called Märta Jörgensen.

Märta Jörgensen was an apprentice gardener when came to the Royal Castle of Tullgarn, in the province of Södermanland in 1900. There, all female employees wore a costume inspired by a traditional dress from Österåker, by decision of the then queen Victoria.

She then married and moved to Dalarna working as a teacher. In Falun she set up the Swedish Women’s National Costume Society, Svenska Kvinnliga Nationaldräkts-Föreningen in 1902. Her goal was to ‘achieve freedom from the dominant foreign fashion through the introduction of a national dress for Swedish women’, that had to be of a simple cut and design, influenced by national romanticism.

She designed two models, one for everyday wear, Blue with a yellow apron as the Swedish flag; the other for special occasions, with a red bodice, representing the Swedish-Norwegian Union (that lasted until 1905).

The Costume Society had over 200 members in 1910, but interest decreased after WW2. Swedish folk costumes enjoyed however a comeback in the 70s. Queen Silvia wearing it on Sweden’s national day in 1983 made it the official national costume.

Side note – Definitions for Swedish folk costumes

Swedish folk costumes are called in various ways: folk folkdräkt (folk dress), landskapsdräkt (national costume), sockendräkt (provincial costume), bygde- or hembygsdräkt (parish or district costume), härads-dräkt (old jurisdictional county costume). The Swedish Museums have decided that the term folkdräkt can only be used for costumes from areas with a well documented, locally distinctive form of dress.

sources:

- Skansen museum (Swedish)

- nationalclothing.com

- Sverigedrakten.se

- Märta Jörgensen biography – skbl.se

- M. Jörgensen, Något om bruket af nationaldräkter ‘On the Use of National Costumes’, 1903

An introduction to Estonian: sister language of Finnish

Estonian is a Finnic language, sharing many similarities with its ‘bigger’ sister Finnish, while being unrelated to all their bigger language neighbours

Scandinavian carnival buns (and where to eat them in the Netherlands)

Cream buns are enjoyed in Nordic and Baltic countries during shrovetide, between January and February. Sweden’s classic semla has almond paste, while other countries variations include jam, vanilla cream, and chocolate icing top.

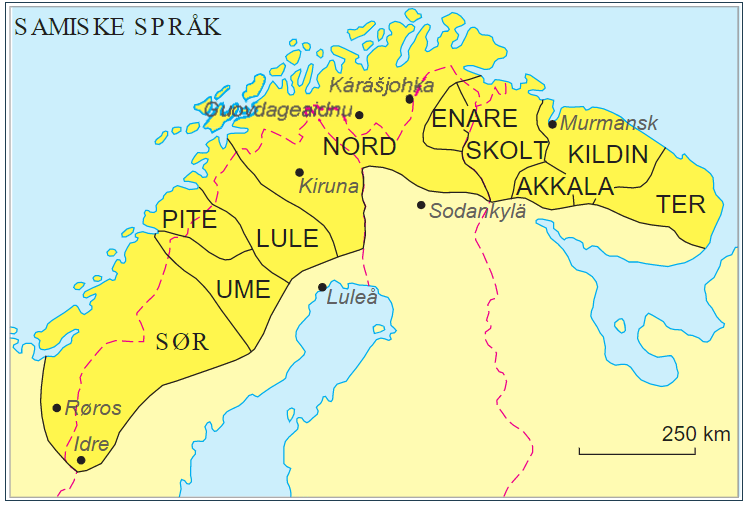

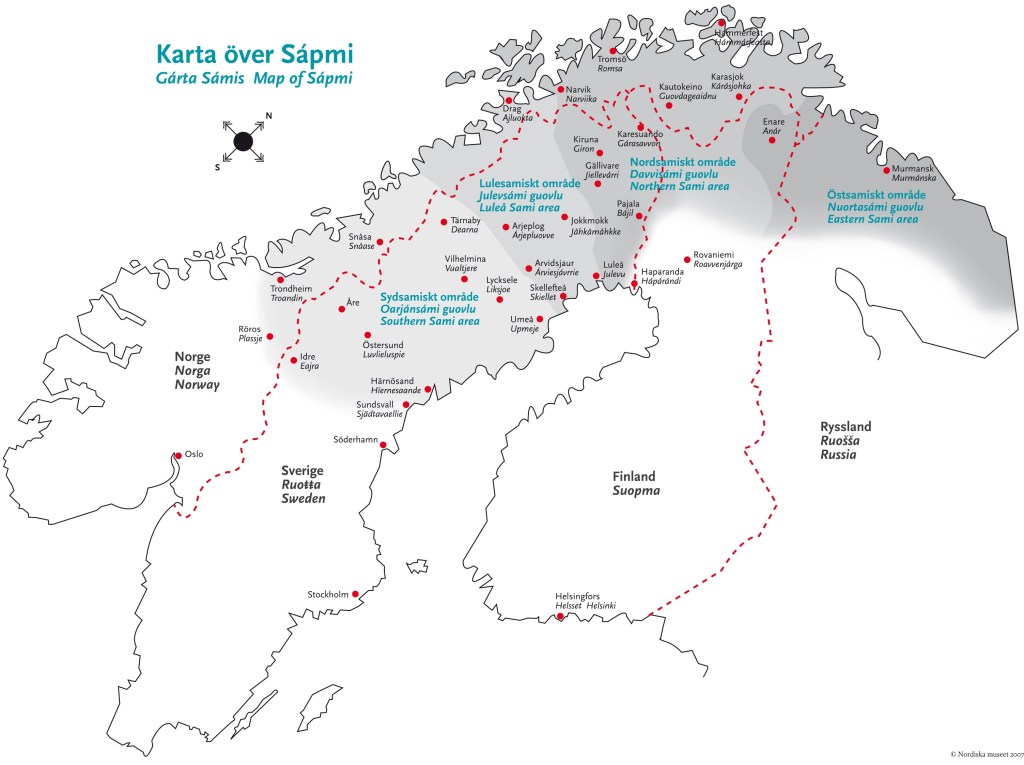

5 symbols of Sami culture

Sámi people, indigenous people of North Scandinavia, have a distinct culture, symbolised by its unique flag and traditional clothing, and part of it are Duodji handicrafts and unique musical expression through yoik.